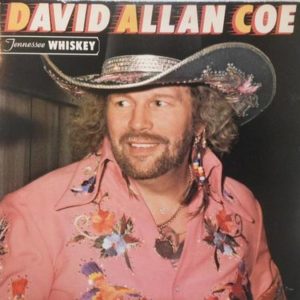

David Allan Coe once wrote that the “Perfect Country and Western Song” would include lyrics about Mama, trains, trucks, prison and getting drunk. A recent false arrest decision issued by Judge Madeline Haikala comes close to meeting those requirements in real life. See Junkins v. DeJong, No. 5:17-cv-00350-MHH, 2020 WL 1083203 (N.D. Ala. Mar. 6, 2020).

As Judge Haikala noted, the facts of this case are truly tragic for Richard Junkins. On March 6, 2015, his family’s mobile home caught fire and burned completely. The water used to extinguish the fire flooded his yard, and his truck became stuck in the mud when the family returned to the home. Around 10 or 11:00 p.m., Mr. Junkins saw a car driving down the road beside his house, and the family dog, “Mr. Bear,” gave chase. Mr. Junkins ran after the dog and waved his arms to get the attention of the driver and prevent Mr. Bear from being struck. Out of breath, he sat down at the curb by his mailbox as the car turned around. Mr. Junkins began walking back to his house and told the driver to “go on.”

The driver was Madison County Sheriff’s Deputy Daniel DeJong. Deputy DeJong walked up the driveway with his gun pulled and shone a flashlight on Mr. Junkins. Mr. Junkins walked towards Deputy DeJong and was 12 to 15 feet away when Deputy DeJong turned his flashlight on Mr. Bear who was laying “beside the area that used to be the door of the home.” Mr. Bear barked twice, but did not move towards Deputy DeJong, who fired twice, killing the dog. Mr. Junkins “became so overcome with emotion that he passed out.”

Deputy DeJong arrested Mr. Junkins for obstructing vehicular or pedestrian traffic and reported that Mr. Junkins was “extremely intoxicated.” Nevertheless, Deputy DeJong acknowledged that he did not have a conversation with Mr. Junkins and did not observe any alcohol containers lying around. Mr. Junkins was acquitted by a jury of the traffic obstruction charge.

Mr. Junkins sued Deputy DeJong for violating his civil rights and committing a false arrest. Deputy DeJong asked Judge Haikala to dismiss that lawsuit using the legal defense of qualified immunity. Under that defense, Deputy DeJong would be entitled to dismissal if he had “arguable probable cause” to arrest Mr. Junkins for any offense. Rather than insisting upon the traffic obstruction charge, Deputy DeJong argued that he could have arrested Mr. Junkins for public intoxication because he “was confronted with an erratically and bizarrely acting Junkins who passed out in front of him for no apparent reason.” Nevertheless, Judge Haikala reached a different conclusion:

No reasonable officer, knowing that he had just entered a citizen’s property, stood 12 to 15 feet from the citizen, and shot the citizen’s dog dead on the citizen’s property, would conclude that the citizen’s loss of consciousness was the result of intoxication. (Doc. 31, ¶¶ 17–19). A reasonable officer in the same circumstances with the same knowledge likely would conclude that Mr. Junkins passed out because he witnessed his dog being killed beside (it would be reasonable to infer) his still-smoldering house.

Junkins, 2020 WL WL 1083203 at *4.

Thus, Judge Haikala refused to dismiss the false arrest claim and ordered the parties to proceed with the discovery phase of the lawsuit. Notably, this case was decided on a motion to dismiss filed by Deputy DeJong. Legally, Judge Haikala was required to believe all of the factual allegations that Mr. Junkins put in his complaint. Potentially, Deputy DeJong could appeal to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals or he could proceed with discovery and attempt to obtain dismiss with a motion for summary judgment after the “real facts” are discovered.